Archive for the 'industrial design' Category

(Posts Archive)

Flexi Pop – Rock and roll synth histories

Posted by homoludo on Feb 10 2011

Posted by homoludo on February 10th, 2011 filed in industrial design, rock and roll, syths, theory, time travel, writing

1 Comment »

Great essay on Industrial design and synth histoy from the ever readable mute magazine. I’ve annotated it with youtube clips of the music mentione. And added a couple I think apply.

Flexi Pop

By Pil and Galia Kollectiv

The introduction of the synthesizer gave PoMo bands the means to replay the history of rock ‘n’ roll with the authenticity knob turned down low. In this month’s music column, Pil and Galia appreciate the flatlands of the synth cover.

An invisible revolution took the United States by storm in the late 1960s – the Flexible Manufacturing System. Perhaps it even had greater implications for the world today than the better known social transformations of the period: the hippies, psychedelic drugs, protests against Vietnam or the student revolt. And yet it has received scant critical attention over the last 40 years since, until recently, the term had little meaning outside engineering conferences on industrial production methods and efficiency. Before 1965, manufacturers tended to concentrate on streamlining industrial procedures to reduce costs and increase productivity. The Fordist model of the assembly line still dominated the market, and companies were busy constructing support systems to enable repetitive, and regularised manufacturing. This approach was immortalised in Henry Ford’s famous words from 1909: ‘Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black’. The ideal customer and the perfect car were both completely predictable and manageable within a rigid plan. It was the responsibility of manufactures to create efficient and controllable products and only then, via advertising, consumer desire for them.

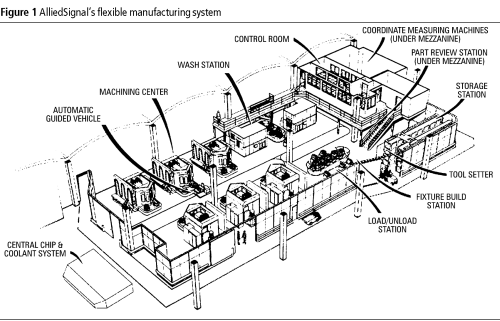

Image: AlliedSignal’s Flexible Manufacturing System

But the Flexible Manufacturing System, developed by Theodore William in Edinburgh in 1965, changed all that. In essence, FMS conceives of industrial manufacturing as a process that can be changed or adapted rapidly to manufacture different products or components at different volumes of production. This required a large number of machines which could be coordinated by a central computer and which would be flexible enough to handle different tasks and absorb sudden changes to volume, speed or design. The influence of this now obvious idea was dramatic. First of all, the products themselves became fluid and Ford’s inevitably black Model T was soon replaced by the seriality of, say, the eight different colours of the iPod nano. The FMS also gave birth to the limited edition product, from the Christmas flavored Starbucks Gingerbread Lattes of December to the heart-shaped Krispy Kreme donut of Valentine’s Day. But, more importantly, FMS was a Copernican revolution that inverted the causality of manufacturing: instead of a product that pre-exists the consumer, manufacturers began to look for the slightest hint of a consumer trend that could be quickly translated into products with a guaranteed market. Since machines were more adaptable and it was possible to easily and rapidly re-organise assembly lines, consumer demands could determine the product.

The influence of these new industrial ideas on politics from the ’70s onwards is evident and well documented. These could be seen reflected in the move away from ideology to a politics based on constant opinion polls and control groups that came to prominence during the Clinton years. But the links between the changing industrial landscape and art and music have not been given due attention and can offer an interesting angle from which to complicate our thinking on postmodernism. Visual art, perhaps, presents a clearer case. In the early 1960s, pop art was premised on an evaluation or even admiration of mass commodities. Pop art exercised several procedures around these commodities: their relocation, following Duchamp, from the supermarket or mass media to the gallery (Warhol, Lichtenstein) and their subsequent re-contextualisation; their material transformation (Oldenburg); or a blurring of borders between background and foreground, the human subject and the world of commodities (Wesselman). All of these mechanisms addressed the commodity as a unique, fixed object and dealt with it only on the level of consumerism, only after it was released to the market as a signifier of desire.

When Warhol was working with pseudo-industrial repetition, he simply duplicated the exact same object, be it a Brillo box, a Campbell soup tin or a print of Marilyn. But the generation of American artists who inherited pop art revised this relationship with the commodity in the late ’60s and throughout the ’70s. Minimalism is still talked about through Michael Fried’s trite notions of ‘relationality’ and ‘literalism’, but it is better viewed as an artistic response to FMS. These artists created flexible and modular systems that enabled them to think of the commodity at a higher level of abstraction. Unlike the Brillo box, Sol LeWitt’s modular cubical structures could be easily re-arranged to create endless variations. Similarly, Dan Flavin’s use of cheap commodities (neon strips) is not so much about their singular identity as objects of desire but their inherent malleability, the fact that the commodity becomes a flexible building block that could be cut to different sizes and thicknesses, and arranged in a variety of ways. Donald Judd’s concrete structures are perhaps the most obvious illustration of this, since the artist used industrial molding techniques to remove the object from its place in a stable relationship with consumers and other objects on the market and re-think it as an abstract flexible system. These artistic practices were not so much attempts to move away from commodity-fetish, from the image and the aesthetic power of the commodity, as readjustments of aesthetic language to account for newer industrial models and the flexibility they demanded.

Popular music can also be looked at through the same prism, but perhaps because a lot of the critical discourse surrounding music is still loyal to ideas of authenticity, individualism, talent and a unique artistic voice, music is rarely discussed in the context of material and industrial production. Here, through the framework of the cover version, a shift can also be observed in the attitude of artists towards other commodities or, more specifically, given pop songs. The repertoire of the bands of the early ’60s, and particularly the ones associated with the first wave of the British invasion, was almost exclusively drawn from the American tunes of the ’50s. The songs these bands covered were mostly associated with the early rock’n’ roll, electric sound of Chicago and the Memphis blues they listened to as teenagers. These covers paid homage to the double take on freedom latent in those songs: at its core, it was the sound of a southern black culture landing on the industrial North with great force. But for the British bands, these were also the sounds of Americana, products of an affluent, youthful, fast culture, the sonic equivalent of the Cadillac or Coca Cola. Cleansed of (racial) context and aural grit, the Rolling Stones’ covers of Chuck Berry functioned in much the same way as Warhol’s empty Brillo boxes, simulacral ciphers of a hyperreal consumer culture.

In the ’70s, however, these appropriations gave way to a lesser known breed of electronic remakes. Stripped down to a bare minimum of broken chords, the minimal synth cover versions that emerged with the rise of the synthesizer reduced the structures of the consumer landscape in the same way as the artists of minimalism. Much of the supposed shock of the new in the punk sound was in fact indebted to a revisiting of, by now, fairly classic rock ‘n’ roll, rubbed raw into the most primitive elements you could get away with, as evidenced by the Sex Pistols’ cover of Eddie Cochran’s ‘C’mon Everybody’, for example. But it was only with the advent of the synthesizer that bands could really discard the guitar-bass-drums aesthetic that defined rock ‘n’ roll and begin to challenge its structure more rigorously. Perhaps the best known precursors of these experiments are Suicide’s re-imaginings of the ’50s as a hollowed out bank of sounds and gestures. Just as Judd, LeWitt and Flavin replaced the supermarket with its empty shell – grey, cold, neon-lit expanses of industrial wasteland – Alan Vega and Martin Rev used the new capacities of the Korg Mini Pops to distill the ghost of Elvis into a pulsating signal, like a fluorescent tube at the end of its life, flashing on and off in a vacant lot. The early ’60s cover version was devoted to content: who you covered was crucial. But for Suicide, Elvis and Chuck Berry were all the same. The noise of motorcycle gangs and the slow dances of a high school prom were boiled down to a psychotic sugary abstraction.

What expressiveness remained in Suicide’s neo-rock ‘n’ roll was excised by the minimal synth bands that followed. When Daniel Miller recorded his Music for Parties in 1980 under the pseudonym Silicon Teens, he wanted to find out what Chuck Berry would sound like if he’d played a synthesizer instead of a guitar. But he was also interested in the fact that new electronic instruments allowed you to prioritise the idea over the execution: you didn’t have to be a songwriter or musician to make music with them. In this he was demonstrating Phil Oakey of the Human League’s well known comment, that synth music was even better than punk because you didn’t even need to learn three chords to play it, just one finger. But he was also following the logic of much concurrent conceptual and minimal art that sought to displace the artist’s gesture using technical fabrication processes borrowed from post-industrial manufacture. The resultant album, featuring covers of ‘Memphis, Tennessee’ and ‘Judy in Disguise’ has been largely consigned to the novelty bin of history, but its interpretation of the canon of rock ‘n’ roll for the wired generation is exemplary. The combination of dead pan delivery with a beat faster than even Chuck Berry’s nimble fingers somehow manages to both delete the decades of musical cliché that had clogged the genre since the ’50s and overwrite it with the immediacy of proto-rock folk music like creole zydeco.

Of course a better known version of the same idea is Flying Lizards’ Top Ten. Following the success of 1979’s ‘Money’, and in light of the relatively quiet reception of a second album more focused on David Cunningham’s experimental music, Top Ten was comprised mainly of reworkings of rock ‘n’ roll classics like ‘Tutti Frutti’ and ‘Dizzy Miss Lizzie’. Here the icy vocals of Sally Peterson, who followed in Deborah Evans-Stickland footsteps after ‘Money”s one hit wonder, were as important as the rudimentary instrumentation. Somehow after decades of sweaty rock ‘n’ roll put through the meat grinder of the culture industry and packaged in wave after wave of retro revival, the clinical, one-tone-fits-all approach seemed better suited to address the age. If rebellion had been fully co-opted, perhaps a kind of pre-empting of the evacuation of content and emotion that was part and parcel of the marketing of youth culture was strategically more useful. Flying Lizards video clips show guitars, drums and keyboards in place, but by no means in conventional use, more frequently being thumped than played, as a pre-recorded soundtrack dictates the pace.

Over in France, Doctor Mix and the Remix’s Wall of Noise, represented another whole album’s worth of standards massacred by post-punks Métal Urbain’s Eric Debris. With the aid of a drum machine, cheap reverb and guitar in overdrive, his rendition of ‘Brand New Cadillac’, but also more recent, alternative classics, like the Stooges’ ‘No Fun’, is notable for its slack attitude, kept in check only by the regimented timing of the machine.

This approach was taken to an extreme across the Atlantic by the Better Beatles, whose payback for the British Invasion on the album Mercy Beat was the cruelest of all. As news of John Lennon’s murder took over the airwaves, the Omaha based group considered the fab four to be an oppressive influence. But instead of going back to the origins of the American rhythm and blues sound that Lennon and McCartney were trying to emulate, they came up with a better strategy. Applying a devastating Midwestern drawl to a playlist of sacred cows, and working in ignorance of the Flying Lizards experiments, they didn’t even attempt to capture the signature melodies of tunes like ‘Penny Lane’, ‘Hello Goodbye’ or ‘Paperback Writer’. Instead, they combined random freeform basslines, basic drumming with simple synth refrains, rehearsed them to death to kill off any freshness or spontaneity, and produced music that sounded nothing like the Beatles beyond the unceremoniously recited lyrics. Often compared with the Residents’ Third Reich and Roll album, the Better Beatles were far less ambitious in their re-tooling of the music establishment. Initially playing around with Beatles songs because they had no original material to work with, they even quite liked the Beatles and just thought the idea was funny. But with the tenacity of a one liner taken too far, they succeeded in both mutilating the transitional moment of popular music’s acceptance as a serious medium and rebuilding the ruins into something that could still be meaningful long after the momentum of the ’60s was truly over. With a few looping riffs, the cover version was thus transformed from a medium of reverential deference to a subversive critical tool, externalising the repressed psychosis of the silly pop refrains that the white rock ‘n’ roll groups of the ’60s bleached of innuendo.

‘To make a rock ‘n’ roll record, technology is the least important thing’, said Keith Richards, meaning that music is an essence removed from its particular historical and material context. This is what allowed the Stones to translate those loud sexual and racial insinuations of early rock ‘n’ roll into slick English, boyish hip sounds. Each southern delta blues number they covered has an irreducible quality beyond its means of production. The minimal synth of the ’70s and ’80s, on the other hand, was busy with the project of deconstructing, rather than transcending the American century. What bands like the Flying Lizards or the Better Beatles aimed to achieve was to look at the recent past of pop music as a structure, and to collapse differences between styles, genres or trends, what Adorno called the manufactured difference between cultural product A versus cultural product B. This was a deliberate strategy of de-mythologisation, moving away from a Debordian conception of spectacular time. Spectacular time, wrote Debord, is the presentation of pseudo-events as significant differences: the past accumulated and consumed like any other commodity:

The production process’s constant innovations are not echoed in consumption, which presents nothing but an expanded repetition of the past. Because dead labor continues to dominate living labor, in spectacular time the past continues to dominate the present.

The interpretation of the past in minimal synth – empty of consumerist desire through technological means that rendered it cold and repetitive – seems to go against Debord’s analysis of popular culture’s attachment to the past. In fact, Debord’s critique itself, because of the changes in manufacturing discussed here and their influence on culture, has become a sort of style in its own right. To be cool in post-Fordist times means not to direct your consumerist desire towards a particular product or a particular moment in history, but to be able to view time, place and culture as flexible systems which can be customised at will.

Superficially, there is something incredibly cynical about the cool, sarcastic appropriations of minimal synth, denying rock ‘n’ roll what little authenticity remained in an ossifying form. At the same time that Tin Pan Valley released their ‘double B-side’ of synthed-up covers of ‘Hanky Panky’ and ‘Yakety Yak’, and that Sun Yama recorded their brilliant cover of Bob Dylan’s ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’, Kraftwerk were developing new ideas for a techno-pop that would leave guitar music behind. But rather than present a new narrative of progress through electronic music, these forgotten bands applied retro-garde methodologies to the existing ones, positing alternative timelines that collapsed the history of popular music as it had been with possible histories of futures past, where Chuck Berry did get to play a Korg instead of a Gibson. When we think of the role of the cover version in contemporary pop idol type reality television competitions, where the aim of each contestant is to decant as much subjectivity as possible into a given text, all the while obscuring the mechanisms which produce this subjectivity in front of our faces, perhaps this non-committal inhabiting of dead forms gains political relevance for today.

Pil and Galia Kollectiv

and…