Archive for the 'theory' Category

(Posts Archive)

Flexi Pop – Rock and roll synth histories

Posted by homoludo on Feb 10 2011

Posted by homoludo on February 10th, 2011 filed in industrial design, rock and roll, syths, theory, time travel, writing

1 Comment »

Great essay on Industrial design and synth histoy from the ever readable mute magazine. I’ve annotated it with youtube clips of the music mentione. And added a couple I think apply.

Flexi Pop

By Pil and Galia Kollectiv

The introduction of the synthesizer gave PoMo bands the means to replay the history of rock ‘n’ roll with the authenticity knob turned down low. In this month’s music column, Pil and Galia appreciate the flatlands of the synth cover.

An invisible revolution took the United States by storm in the late 1960s – the Flexible Manufacturing System. Perhaps it even had greater implications for the world today than the better known social transformations of the period: the hippies, psychedelic drugs, protests against Vietnam or the student revolt. And yet it has received scant critical attention over the last 40 years since, until recently, the term had little meaning outside engineering conferences on industrial production methods and efficiency. Before 1965, manufacturers tended to concentrate on streamlining industrial procedures to reduce costs and increase productivity. The Fordist model of the assembly line still dominated the market, and companies were busy constructing support systems to enable repetitive, and regularised manufacturing. This approach was immortalised in Henry Ford’s famous words from 1909: ‘Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black’. The ideal customer and the perfect car were both completely predictable and manageable within a rigid plan. It was the responsibility of manufactures to create efficient and controllable products and only then, via advertising, consumer desire for them.

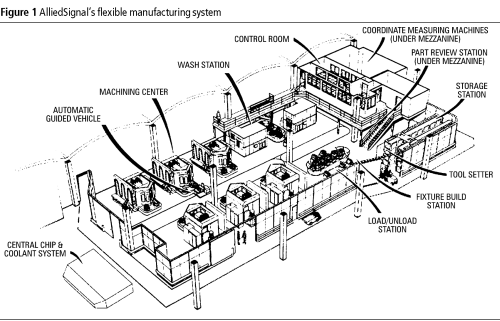

Image: AlliedSignal’s Flexible Manufacturing System

But the Flexible Manufacturing System, developed by Theodore William in Edinburgh in 1965, changed all that. In essence, FMS conceives of industrial manufacturing as a process that can be changed or adapted rapidly to manufacture different products or components at different volumes of production. This required a large number of machines which could be coordinated by a central computer and which would be flexible enough to handle different tasks and absorb sudden changes to volume, speed or design. The influence of this now obvious idea was dramatic. First of all, the products themselves became fluid and Ford’s inevitably black Model T was soon replaced by the seriality of, say, the eight different colours of the iPod nano. The FMS also gave birth to the limited edition product, from the Christmas flavored Starbucks Gingerbread Lattes of December to the heart-shaped Krispy Kreme donut of Valentine’s Day. But, more importantly, FMS was a Copernican revolution that inverted the causality of manufacturing: instead of a product that pre-exists the consumer, manufacturers began to look for the slightest hint of a consumer trend that could be quickly translated into products with a guaranteed market. Since machines were more adaptable and it was possible to easily and rapidly re-organise assembly lines, consumer demands could determine the product.

The influence of these new industrial ideas on politics from the ’70s onwards is evident and well documented. These could be seen reflected in the move away from ideology to a politics based on constant opinion polls and control groups that came to prominence during the Clinton years. But the links between the changing industrial landscape and art and music have not been given due attention and can offer an interesting angle from which to complicate our thinking on postmodernism. Visual art, perhaps, presents a clearer case. In the early 1960s, pop art was premised on an evaluation or even admiration of mass commodities. Pop art exercised several procedures around these commodities: their relocation, following Duchamp, from the supermarket or mass media to the gallery (Warhol, Lichtenstein) and their subsequent re-contextualisation; their material transformation (Oldenburg); or a blurring of borders between background and foreground, the human subject and the world of commodities (Wesselman). All of these mechanisms addressed the commodity as a unique, fixed object and dealt with it only on the level of consumerism, only after it was released to the market as a signifier of desire.

When Warhol was working with pseudo-industrial repetition, he simply duplicated the exact same object, be it a Brillo box, a Campbell soup tin or a print of Marilyn. But the generation of American artists who inherited pop art revised this relationship with the commodity in the late ’60s and throughout the ’70s. Minimalism is still talked about through Michael Fried’s trite notions of ‘relationality’ and ‘literalism’, but it is better viewed as an artistic response to FMS. These artists created flexible and modular systems that enabled them to think of the commodity at a higher level of abstraction. Unlike the Brillo box, Sol LeWitt’s modular cubical structures could be easily re-arranged to create endless variations. Similarly, Dan Flavin’s use of cheap commodities (neon strips) is not so much about their singular identity as objects of desire but their inherent malleability, the fact that the commodity becomes a flexible building block that could be cut to different sizes and thicknesses, and arranged in a variety of ways. Donald Judd’s concrete structures are perhaps the most obvious illustration of this, since the artist used industrial molding techniques to remove the object from its place in a stable relationship with consumers and other objects on the market and re-think it as an abstract flexible system. These artistic practices were not so much attempts to move away from commodity-fetish, from the image and the aesthetic power of the commodity, as readjustments of aesthetic language to account for newer industrial models and the flexibility they demanded.

Popular music can also be looked at through the same prism, but perhaps because a lot of the critical discourse surrounding music is still loyal to ideas of authenticity, individualism, talent and a unique artistic voice, music is rarely discussed in the context of material and industrial production. Here, through the framework of the cover version, a shift can also be observed in the attitude of artists towards other commodities or, more specifically, given pop songs. The repertoire of the bands of the early ’60s, and particularly the ones associated with the first wave of the British invasion, was almost exclusively drawn from the American tunes of the ’50s. The songs these bands covered were mostly associated with the early rock’n’ roll, electric sound of Chicago and the Memphis blues they listened to as teenagers. These covers paid homage to the double take on freedom latent in those songs: at its core, it was the sound of a southern black culture landing on the industrial North with great force. But for the British bands, these were also the sounds of Americana, products of an affluent, youthful, fast culture, the sonic equivalent of the Cadillac or Coca Cola. Cleansed of (racial) context and aural grit, the Rolling Stones’ covers of Chuck Berry functioned in much the same way as Warhol’s empty Brillo boxes, simulacral ciphers of a hyperreal consumer culture.

In the ’70s, however, these appropriations gave way to a lesser known breed of electronic remakes. Stripped down to a bare minimum of broken chords, the minimal synth cover versions that emerged with the rise of the synthesizer reduced the structures of the consumer landscape in the same way as the artists of minimalism. Much of the supposed shock of the new in the punk sound was in fact indebted to a revisiting of, by now, fairly classic rock ‘n’ roll, rubbed raw into the most primitive elements you could get away with, as evidenced by the Sex Pistols’ cover of Eddie Cochran’s ‘C’mon Everybody’, for example. But it was only with the advent of the synthesizer that bands could really discard the guitar-bass-drums aesthetic that defined rock ‘n’ roll and begin to challenge its structure more rigorously. Perhaps the best known precursors of these experiments are Suicide’s re-imaginings of the ’50s as a hollowed out bank of sounds and gestures. Just as Judd, LeWitt and Flavin replaced the supermarket with its empty shell – grey, cold, neon-lit expanses of industrial wasteland – Alan Vega and Martin Rev used the new capacities of the Korg Mini Pops to distill the ghost of Elvis into a pulsating signal, like a fluorescent tube at the end of its life, flashing on and off in a vacant lot. The early ’60s cover version was devoted to content: who you covered was crucial. But for Suicide, Elvis and Chuck Berry were all the same. The noise of motorcycle gangs and the slow dances of a high school prom were boiled down to a psychotic sugary abstraction.

What expressiveness remained in Suicide’s neo-rock ‘n’ roll was excised by the minimal synth bands that followed. When Daniel Miller recorded his Music for Parties in 1980 under the pseudonym Silicon Teens, he wanted to find out what Chuck Berry would sound like if he’d played a synthesizer instead of a guitar. But he was also interested in the fact that new electronic instruments allowed you to prioritise the idea over the execution: you didn’t have to be a songwriter or musician to make music with them. In this he was demonstrating Phil Oakey of the Human League’s well known comment, that synth music was even better than punk because you didn’t even need to learn three chords to play it, just one finger. But he was also following the logic of much concurrent conceptual and minimal art that sought to displace the artist’s gesture using technical fabrication processes borrowed from post-industrial manufacture. The resultant album, featuring covers of ‘Memphis, Tennessee’ and ‘Judy in Disguise’ has been largely consigned to the novelty bin of history, but its interpretation of the canon of rock ‘n’ roll for the wired generation is exemplary. The combination of dead pan delivery with a beat faster than even Chuck Berry’s nimble fingers somehow manages to both delete the decades of musical cliché that had clogged the genre since the ’50s and overwrite it with the immediacy of proto-rock folk music like creole zydeco.

Of course a better known version of the same idea is Flying Lizards’ Top Ten. Following the success of 1979’s ‘Money’, and in light of the relatively quiet reception of a second album more focused on David Cunningham’s experimental music, Top Ten was comprised mainly of reworkings of rock ‘n’ roll classics like ‘Tutti Frutti’ and ‘Dizzy Miss Lizzie’. Here the icy vocals of Sally Peterson, who followed in Deborah Evans-Stickland footsteps after ‘Money”s one hit wonder, were as important as the rudimentary instrumentation. Somehow after decades of sweaty rock ‘n’ roll put through the meat grinder of the culture industry and packaged in wave after wave of retro revival, the clinical, one-tone-fits-all approach seemed better suited to address the age. If rebellion had been fully co-opted, perhaps a kind of pre-empting of the evacuation of content and emotion that was part and parcel of the marketing of youth culture was strategically more useful. Flying Lizards video clips show guitars, drums and keyboards in place, but by no means in conventional use, more frequently being thumped than played, as a pre-recorded soundtrack dictates the pace.

Over in France, Doctor Mix and the Remix’s Wall of Noise, represented another whole album’s worth of standards massacred by post-punks Métal Urbain’s Eric Debris. With the aid of a drum machine, cheap reverb and guitar in overdrive, his rendition of ‘Brand New Cadillac’, but also more recent, alternative classics, like the Stooges’ ‘No Fun’, is notable for its slack attitude, kept in check only by the regimented timing of the machine.

This approach was taken to an extreme across the Atlantic by the Better Beatles, whose payback for the British Invasion on the album Mercy Beat was the cruelest of all. As news of John Lennon’s murder took over the airwaves, the Omaha based group considered the fab four to be an oppressive influence. But instead of going back to the origins of the American rhythm and blues sound that Lennon and McCartney were trying to emulate, they came up with a better strategy. Applying a devastating Midwestern drawl to a playlist of sacred cows, and working in ignorance of the Flying Lizards experiments, they didn’t even attempt to capture the signature melodies of tunes like ‘Penny Lane’, ‘Hello Goodbye’ or ‘Paperback Writer’. Instead, they combined random freeform basslines, basic drumming with simple synth refrains, rehearsed them to death to kill off any freshness or spontaneity, and produced music that sounded nothing like the Beatles beyond the unceremoniously recited lyrics. Often compared with the Residents’ Third Reich and Roll album, the Better Beatles were far less ambitious in their re-tooling of the music establishment. Initially playing around with Beatles songs because they had no original material to work with, they even quite liked the Beatles and just thought the idea was funny. But with the tenacity of a one liner taken too far, they succeeded in both mutilating the transitional moment of popular music’s acceptance as a serious medium and rebuilding the ruins into something that could still be meaningful long after the momentum of the ’60s was truly over. With a few looping riffs, the cover version was thus transformed from a medium of reverential deference to a subversive critical tool, externalising the repressed psychosis of the silly pop refrains that the white rock ‘n’ roll groups of the ’60s bleached of innuendo.

‘To make a rock ‘n’ roll record, technology is the least important thing’, said Keith Richards, meaning that music is an essence removed from its particular historical and material context. This is what allowed the Stones to translate those loud sexual and racial insinuations of early rock ‘n’ roll into slick English, boyish hip sounds. Each southern delta blues number they covered has an irreducible quality beyond its means of production. The minimal synth of the ’70s and ’80s, on the other hand, was busy with the project of deconstructing, rather than transcending the American century. What bands like the Flying Lizards or the Better Beatles aimed to achieve was to look at the recent past of pop music as a structure, and to collapse differences between styles, genres or trends, what Adorno called the manufactured difference between cultural product A versus cultural product B. This was a deliberate strategy of de-mythologisation, moving away from a Debordian conception of spectacular time. Spectacular time, wrote Debord, is the presentation of pseudo-events as significant differences: the past accumulated and consumed like any other commodity:

The production process’s constant innovations are not echoed in consumption, which presents nothing but an expanded repetition of the past. Because dead labor continues to dominate living labor, in spectacular time the past continues to dominate the present.

The interpretation of the past in minimal synth – empty of consumerist desire through technological means that rendered it cold and repetitive – seems to go against Debord’s analysis of popular culture’s attachment to the past. In fact, Debord’s critique itself, because of the changes in manufacturing discussed here and their influence on culture, has become a sort of style in its own right. To be cool in post-Fordist times means not to direct your consumerist desire towards a particular product or a particular moment in history, but to be able to view time, place and culture as flexible systems which can be customised at will.

Superficially, there is something incredibly cynical about the cool, sarcastic appropriations of minimal synth, denying rock ‘n’ roll what little authenticity remained in an ossifying form. At the same time that Tin Pan Valley released their ‘double B-side’ of synthed-up covers of ‘Hanky Panky’ and ‘Yakety Yak’, and that Sun Yama recorded their brilliant cover of Bob Dylan’s ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’, Kraftwerk were developing new ideas for a techno-pop that would leave guitar music behind. But rather than present a new narrative of progress through electronic music, these forgotten bands applied retro-garde methodologies to the existing ones, positing alternative timelines that collapsed the history of popular music as it had been with possible histories of futures past, where Chuck Berry did get to play a Korg instead of a Gibson. When we think of the role of the cover version in contemporary pop idol type reality television competitions, where the aim of each contestant is to decant as much subjectivity as possible into a given text, all the while obscuring the mechanisms which produce this subjectivity in front of our faces, perhaps this non-committal inhabiting of dead forms gains political relevance for today.

Pil and Galia Kollectiv

and…

Digital playtime and Computer love

Posted by homoludo on Jun 10 2010

Posted by homoludo on June 10th, 2010 filed in flyers, gigs, theory

Comment now »

Two strangely similar but very different gigs this weekend. Brother Ludo and I playing as Homoludo on the bill with Subversus this Friday in support of Basek (mix to check) at mad chiptune and video game night Gamepak. Also playing elsewhere in the venue that night are Martyn, who with Kode 9(link to a good review of his dissapointing book, Sonic Warfare) played my fav set at Block this year) and Dj Yoda…which is nice. And on Sat I think I’m playing at some diy media party thing also but will post when I know more.

And (again) on Sunday, Big Monster Love, sings of history in the digital age and love as social networking in Bewley’s Grafton street.

Responsibility

Posted by homoludo on May 27 2009

Posted by homoludo on May 27th, 2009 filed in theory

Comment now »

k-Punk on responsibility and it’s lack at institutional, corporate and individual levels. VERY worth reading if you’re watching and experiencing the various power networks in Ireland justify, plan and entrench their survival.

Hard Wired, Hardcore Continuum

Posted by homoludo on Mar 04 2009

Posted by homoludo on March 4th, 2009 filed in Bassline, bleepy, grime, hardcore, Hardcore continuum, history, theory, time travel, writing

5 Comments »

I remember reading Wire articles and thinking this reads/sounds amazing , if only it was the future and I could just click and listen to the music. Well, here’s Simon Reynolds with a pretty amazing explanation/history of the hard core continuum and doing just that(using tunes to demonstrate). It’s kind of beautiful, so I’m reposting it (I left out the postscript. It kind of ruins the tone, but for the persistent here it is)

THE HARDCORE CONTINUUM,

or,

(a)Theory and Its Discontents

The text of a talk by Simon Reynolds delivered at FACT, Liverpool, Wednesday 11th February 2009.

PLUS

notes for points to be brought up during the dialogue segment with Mark Fisher but weren’t owing to time running out

PLUS

afterthoughts on the past, present and future of the hardcore continuum

^^^^^^^^

Thanks for coming out tonight. Thanks to curator Heather Corcoran and FACT for inviting me here, thanks also to my friend and colleague Mark Fisher from the Wire for his involvement, we will be having a discussion in a little while, I know he has a lot to say, lots of angles, and then we’ll be throwing it open to questions from the audience.

But first, I’m going to talk about this little thing called the Hardcore Continuum Theory.

The first thing to note is that it’s not a theory — any more than Australia is a theory, or Jupiter is a theory. It’s a fact, an objectively existent entity — all I did was come up with a name for it, in the same way that someone came up with the name Australia and now the Australians are lumbered with it.

What the term describes is empirically verifiable, there is a body of testimony and reportage, all you need to do is talk to people involved at the various stages of this phenomenon–from hardcore through jungle and UK garage to grime, dubstep and bassline, and the continuum-ness of it is clear — funky house, the latest emissions from the continuum is more debatable, it is a moot point whether that signifies the crumbling of the continuum. I’m not wholly convinced by that argument, but equally I’m not wholly convinced by the music, I’m sure we can discuss this heatedly later.

Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not opposing to myself to theory, I’m all for theorizing, to me theory is the spice of critical life — and the theory aspect to the Continuum discussion relates to the analysis of how this subcultural and musical entity came into being, what governs its development and mutation, where it fits into the grand scheme of music, and then there’s speculation about where it might go next, which is fun but foolhardy because the continuum, in my experience, will always ambush you with some new twist, a mind-wrenching paradigm shift.

Theory or a critical perspective also comes into the picture when you get to some kind of assessment, or claim, in terms of what it means, what it’s worth in the grand scheme of things–which I will get to doing later on

There is also perhaps a macro level, or meta level, where we can talk about how understanding music in terms of continuums applies beyond this specific example to other kinds of musical traditions, scenes, subcultures — a sketch towards some kind general theory of the evolution of genres in popular music.

But okay, let’s start with the basic facts, what I’m asserting precedes theory, the undeniable evidence. What is it that makes this continuum… continuous?

First there is a continuity of infrastructure — as you came and took your seats some of you will have heard that track “Pirates Anthem” by Home T, Coco Tea, Shabba Ranks — that is from 1989, 1990 I think, so just at the very moment before the continuum gets going– and a key part of the infrastructural foundation for the continuum is pirate radio — there are pirate radio stations that have shifted their music policies as the scene’s music has gone through drastic changes — a fantastic example here is Rinse FM, everyone I’m sure is aware that this stationshas been the don of grime and dubstep for the entire Noughties — well Rinse FM started in 1994, it was a jungle pirate originally — Rinse as you know if were on the scene then is an absolutely key jungle buzzword — as in “rinse out the sound”, “absolutely rinsing set Mr DJ” — unlike for example Kool FM, which was the leading jungle pirate probably and which stuck with jungle, Rinse went garage in 1999 — but that was at a point where garage was already becoming an MC dominated music, they had crews like Pay As You Cartel on their station, garage rap some called the sound then, and of course that turned into grime — so Rinse becomes the leading station for grime and dubstep — and right now Rinse is dominated by funky house and I believe is the leading pirate in London for funky — now that fact in itself would seem to prove funky is part of the continuum.

Pirate radio is a key part of the enduring infrastructure, you also get certain promoters and clubs that carry on through all the musical changes — record stores that change with each new shift, like Rhythm Division in the East End of London — I don’t know if dubplates are as important now but for a long, long stretch of the continuum’s existence, deejays played a huge proportion of the music on their sets in the form of dubplates, and there was a specific place you went to get your dubplates cut and that was Music House in London.

Another running thread is the continuity of rituals — the rewind, the role of the MC as accompaniment to the DJ. You do not get the rewind or the MC in forms of UK dance music such as house or techno or trance — it’s unique to the hardcore, jungle, garage tradition — it comes from the sound system reggae-dancehall tradition originally, obviously.

What else is continuum-ous? There is a continuity of personnel, certain key figures keep cropping up, in a bit I will get into actual examples of artists who went through several successive phases of this music, changing their styles, you might say opportunistically but then if you said that you’d not be understanding the essence of this music, which is constant forward movement — in with the new, out with the old.

There’s not many figures who go all the way through, you tend to get people going from hardcore to jungle to UK garage… or from jungle to garage to grime…. or garage to grime to funky. HOWEVER I do have a jackpot example, which DJ Footloose, who actually runs through the entire history of the scene — he started deejaying in 1992, played jungle clubs like Telepathy, the Roast, Thunder and Joy, he played on Kool FM, then in ’98 he switched to garage, played on Déjà Vu and Freek two of the big speed garage stations, later graduating to shows on Kiss FM… he seems to have skipped grime but is currently one of the leading DJs for funky house, producing tracks and he presents the funky house show on 1xtra. So here you have a figure who must be getting on a bit now, in his late 30s, who runs the whole gamut from ardkore to funky house. Footloose can answer Zomby’s question’s “where were you in 92?”. Because he was right there in the thick of the scene, and in 09 he’s still there, in the thick of the scene. And that’s because it is the same scene, essentially, fundamentally: the hardcore continuum.

There is also a continuity of population, the punters move with each new style shift … you’ll not find many people who were into hardcore in 1990 and are into dubstep or funky now, that’s because a lot of people drop out as they get to mid-thirties if not earlier, they can’t hack the lifestyle any longer, but you will find a few, and there’s many many people who went the whole journey from rave through jungle to garage and the early days of grime — the grime MCs for instance were all influenced by the jungle MCs–Skibadee, Shabba, GQ, Dett, Moose — that’s who they cite as their prime influences, as opposed to American rappers.

Equally significant is the continuity of geography — for most of the continuum’s history, London is central. Greater London bleeding out into the Croydon type suburbs in the South and up into Essex and Hertfordshire. Which is where I’m from. Now strangely Hertfordshire is a stronghold of the continuum: a key jungle label Moving Shadow was based there as were artists like Omni Trio and also Source Direct who came from St Albans of all places. But that is really because of the new town, overflow town syndrome, you had proper Londoners, often East Londoners being shipped out to Herts, Kent, Surrey…

So it’s London and surrounding counties. But it’s never been just London, for sure there’s been times when it has contracted pretty tight on the capital, even on the East End… but right at the start you had the North East involved, with bleep: that was the South Yorkshire and West Yorks cities, industrial towns with a good multicultural mix, a strong black population. Also Leicester where Formation Records and DJ SS were based.

For similar multicultural reasons you also had Bristol running through the whole lifetime of the continuum pretty much, from early jungle to dubstep — Bristol is the second city of dubstep after London.

And you had the Midlands being a stronghold… Coventry in particular. Now for some reason not the North West really… I don’t know why… Perhaps someone in the audience has a theory they can advance why Liverpool and Manchester haven’t contributed much to the hardcore continuum.

So without wishing to be too Londoncentric, I’d say the continuum, as a creative force as opposed to people just liking the music, which you get all over — all over the country, and all over the world — but as a cultural engine that produces the music, it has been about London and the most London-like cities in the UK, in terms of their multiculturalism, their multiracialism.

Finally and perhaps most crucially there’s been a continuity of sound and of attitude.

But before I get into that though, let’s go right back to the start:

1989-1990, the UK rave scene is exploding — at first it was really totally oriented around imports, house tracks from Chicago, techno from Detroit, garage and Todd Terry type hip-house stuff from New York… people in Britain started to imitate that music but it was a pretty straight copy at first and pretty second-rate, with a few exceptions, we must big up A Guy Called Gerald and 808 State and a few others ….. But really the first time the UK comes up with its own spin on house and techno is towards the end of 1989 – almost 20 years ago. Strangely how they do that is adding a bunch of elements that are actually not indigenous to the U.K. but would never have been let into the mix in Chicago or Detroit — ideas from hip hop and electro, the booming 808 basslines… ideas from dub reggae and dancehall…. The first totally uniquely UK rave music stuff was bleep — or bleep and bass as some called it — from Yorkshire and the West Midlands: Unique 3, Sweet Exorcist, LFO, Nightmares on Wax, names that will, if you’re a certain age, send a memory rush rippling down your spine.

Unique 3 were B-boys from Bradford, some of their early tracks have rapping on, not very good rapping admittedly, but there’s a hip house feel, you could even hear those tunes as future ghosts of grime. They also had heavy heavy sub-bass, again that’s like a future ghost of dubstep except it’s also, simultaneously a past-ghost — an echo down the years of sound systems mashing it down in Kingston, Jamaica.

Meanwhile at around the same time you had Shut Up and Dance in London, also hip hop influenced, big Public Enemy fans, making what they called “fast hip hop” . but almost against their own intentions their tracks became rave anthems. Shut Up and Dance were a group and a label, they had acts like the Ragga Twins who mashed together dancehall chat and searingly harsh European style techno, ragga-techno it was essentially, they weren’t alone doing that, there was Demon Boyz, who had a track called “Junglist” if I remember correctly, and there was Rebel MC.

And the Shut Up and Dance sound with the looped, uptempo, sped up breakbeats, some people called that ‘breakbeat house’, there were other groups doing that like Blapps Posse as well. This breakbeat house sound was the roots of jungle . And in fact a lot of the bleep records, although done with drum programming not breakbeats, had a skippy, syncopated feel to the rhythms, it wasn’t a straight four to the floor house feel, it was almost like breakbeats done with drum machines.

Now breakbeat house and bleep, these UK-specific sounds, they come to be known as hardcore for a variety of reasons. The music is harder and more banging and more overtly druggy than the American stuff. Also the UK made tracks tend to really appeal to the most hardcore, full-on, pill-necking, drug monster ravers. It’s hardcore cos the production values are quite low , it’s white label music, not very polished, raw sounding, so it stays underground, most of it… It’s not on the radio, or at least it is, but only on pirate radio.

At this stage people talk about hardcore house , that was actually a term believe it or not, or hardcore techno, then soon hardcore rave, and then just hardcore. Ardkore. Warp, who we think of in terms of electronic listening music, in those days they were pioneers of bleep and they called themselves hardcore early on, that’s where they situated themselves.

Now the London version of hardcore would prove more influential in the long run than Northern bleep, because bleep was still quite acid and techno in vibe, quite dark and serious and minimal, but what Shut up and Dance brought in was this thing of very very cheeky samples from mainstream pop, massive chunks of uncleared samples — and also SUAD loved movie soundtracks, they loved an orchestral sample — and that is something that runs through the entire sweep of the continuum, you get funny little string refrains and pizzicato motifs in hardcore, in jungle, in 2step, in early grime, right now in bassline…..

A good recent example is Dok’s “Rapid Speed” with its swashbuckling orchestral parts. Or from a few years ago Imp Batch’s track “Gype Riddim” aka “Singalong” which is supposed to be a cut up of Prokofiev or somebody like that. This classical, orchestral thing is something YOU DO NOT GET IN PROPER HOUSE MUSIC, PROPER TECHNO, but this is improper music, it breaks the rules of propriety and property… if it’s not nailed down it will be stolen by the hardcore continuum —

The poppy and chintzy sub-classical elements explain why you get this weird mix of rude and cheesy, ruffneck and sentimental, dark and soppy, running through the music, and you can pick that up from the visuals mostly scanned from my own collection that are showing on the big screen behind me — this can be a tacky subculture.

Another thing that you get with the hardcore continuum that you don’t get nearly so much with other forms of dance music, is that it has a sense of humour. A great spirit of playfulness. It’s not afraid to be daft. To be silly, even.

One reason the breakbeats catch on more is they’re initially easier to do than programming the drum machines so all kinds of teenage tearaways get involved and slam out a quick white label, make some fast money.

By ’92 we’ve got piano riffs from Italian house and Belgian techno terror noises in the mix, and chartpop samples and movie score elements and all kinds of odd samples taken from these kids’s parents’ record collections — Pink Floyd and old folk rock, you name it. But the basic coordinates of hardcore in this defining year of 1992 are a four way collision of hip hop and techno, reggae and house… It’s like a multiple pile-up at a crossroads. And the BIG BANG releases this surge of energy: you have this crazy-fast evolution of hardcore into jungle, the development of breakbeat science and bass science — the breaks get sped up, edited, processed, fantastically complex yet jagged yet groovy rhythms— the bass gets more strange and peculiar, molded and gloopy, yet also punishing, and yet also heavy in a rootical sense, the dub reggae sense, there’s a skanking feel in there too

Jungle continues on this path getting more intricate and extreme and pursuing lots of different directions and flavours, and by 1994-95 they’re calling it drum’n’bass, (an act of self-inflicted gentrification if you ask me).

Next comes the big schism, the big paradigm shift, the thing that some people can’t get their heads around, the switch to speed garage, which is 1996-1997.

It’s actually a parting of the ways, drum’n’bass continues on its own path, which I see as a river branching off the continuum, and meanwhile a huge proportion of the London audience for jungle switches to a new sound UK garage or speed garage. It wasn’t actually a new sound, if had existed in parallel with jungle for a few years in the mid-90s — if you’d gone to a jungle club in those days, the chances are the second room, the chill out room, would have had garage, soulful house mostly made in America — I never understood it at the time, it seemed a bit bland to me, but it was a mellower, more R&B sound, and gradually those second rooms got more popular as the drum’n’bass in the main arena got more punishing. The garage room would increasingly be where the women were. And the guys started thinking, hmmm I want to be in the room where the girls are.

Now at the same time pirates were playing garage at certain off peak times of the day and deejays who’d been through hardcore and jungle were really ruffing up the New York garage tracks, playing them at plus 8, playing the dubstrumentals — the dub instrumental versions on the flipside –getting MCs to chat on top — then they started making their own tracks, they were still sexy and much slower than jungle, but faster and tougher than New York garage — and the producers would work in some jungle sounds: heavy basslines, ragga chat, mad effects. And that mix was called speed garage.

The best explanation of how jungle turned into UK garage and almost inverted itself while staying the same is the way the drum’n’bass label No U Turn opened a garage imprint called Turn U On. That’s almost like a palindrome or something. It would be even better if No U Turn On had actually put out some killer garage that was anything near as good as their techstep releases. But that bit of wordplay captures the paradigm shift perfectly.

I’m going to take a pause for the cause here and play some music, to show the evolution and how certain figures recur at different stages:

Foul Play, “Dubbing U”, from Vol. 2, 1992

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6gEEJeXnRfM

Now that was Foul Play, “Dubbing U”, from 1992. You can hear the reggae influence in there. “Dubbing U” is actually one of Burial’s favourite tunes, a real ancestral track for him. Foul Play were a trio but Steve Gurley was perhaps at this point the driving force it would be fair say. And it’s Steve Gurley whose trajectory we’re going to follow.

Steve Gurley leaves Foul Play, lets them keep the name and he becomes Rogue Unit, under that name he does a lot of great remixes. Including this, which is effectively a bootleg remake of an Eighties R&B song by Princess “Say I’m Your Number One”, not sure if it this remake was ever actually released, I have it on an old jungle compilation.

Princess, “Say I’m Your Number 1” (Exclusive Dubplate Special/Rogue Unit remix)

[I can’t find the actual remix in question on the web but strangely there is another track by Rogue Unit from 1995 that samples “Say I You’re Number One” — Rogue Unit, “Good To You” — I guess he really, really loved that Princess tune!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGF82XgnPpA — This version is quite different — really really fierce, mashed-Amens style, good in its own way but nothing compares to the Exclusive Dubplate Special.]

Now I should have said one thing running through the whole of this music is actually soul — female-voiced, usually, not always, but usually a diva from an old r&B or deep house record – the vocals won’t be left alone like an American house producer would tend to, though, in the UK we mess around with stuff, so the voice gets get chopped up and resequenced, producers on the continuum become experts in creating a whole new emotional emphasis, as on the Princess track, the original is completely different in vibe, you can find it on youtube pretty easily and it’s a much more placid song, whereas the Steve Gurley remake has this bursting edge-of-hysteria quality, which is much more suited to rave culture… the kind of feelings that come out of Ecstasy.

And then as we get to UK garage and 2step more and more there’s processing on the vocals, there’s micro-editing, turning the human voice into percussion, vocal science as a friend of mine, Bat, dubbed it — But even through all this cyborg manipulation which it’s always fun to talk about, always there is this soul power –a kind of hypersoul, maybe — and that runs through the whole continuum, from hardcore to bassline — and for various cultural reasons that are interesting to think about, it’s the female voice that is the privileged representation of bliss — so we have this current of feminine pressure running through the continuum — indeed when the voices start to drop out of the music completely, then I think we’re in trouble, then it’s starting to be a river branching off the continuum, as with drum and bass, as with dubstep. Then it starts to have international appeal, the less soulful it is — funnily enough. Your international white boys contingent don’t like the divas, it doesn’t compute for them, they think that kind of singing makes it pop music, or R&B. And they probably haven’t done enough Ecstasy to feel that hypersoul rush.

And then in the garage era Steve Gurley — perfect name really for someone operating with feminine pressure and divas — he pops up again using his own name doing remixes like this one

Baffled and Operator, “Things Are Never (Steve Gurley Remix”, 1998

audible here http://classichousemusic.blogspot.com/2008/01/operator-baffled-things-are-never-steve.html

[check out also this equally massive Gurley remix of the era — http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JdccX4BJCqc — his 2step version of Lenny Fontana’s “Spirit of the Sun”]

So once again, as with the first two tracks, you can hear the reggae thing in the bass, and the whole vibe is sensual yet ominous, the lyric goes “things are never/ quite the way/they seem” which is tinged with paranoia. Sexy dark garage is what I’d call this track.

Now after I finished this CD for the talk I stumbled on a track by Steve Gurley called ‘Hotboys’, it appears on a compilation CD called The Roots of Dubstep, put out by Tempa Records…

Steve Gurley, Hotboys, circa 2000

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7GHPw1VNiFI

And in fact tying in with my thesis about dubstep losing the diva vocals, that track doesn’t have a vocal on in fact.

So there you have one producer who goes from hardcore through jungle, through speed garage, to be a foundational figure in dubstep, and for all I know he’s still out

there, making funky house tracks. Steve Gurley: he’s not that well known outside the scene, but he is one of the all time pantheon.

Next up, another god-like figure, Chris MacFarlane. First I know of Chris Mac is this track on the Ibiza label from ’92, he’s calling himself Bad Girl, that’s just one of his alter-egos, and the track is “Bad Girl.”

Bad Girl, “Bad Girl” (Ibiza, 1992)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0eaAM6gua9E

So that’s hardcore, with the sped-up squeaky chipmunk voice, but quite a junglistic feel, jungle techno they’d have called that it in 92, and you would never get that kind of bassline in techno from outside the UK.

Next he’s gone from being Bad Girl to calling himself Potential Bad Boy, here’s a burst of “Let’s Go” from the Work the Box EP, this would be late 93 and it’s a more junglistic track.

Potential Bad Boy, “Let’s Go”, Work the Box EP, Limited Edition E, 1993

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gaG92iT6bRM

And here he is again in 1998, under his own name finally, Chris Mac, “Plenty”, doing 2step garage.

Chris Mac, Plenty, 1998

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DdW48JSQAtg

That’s 2step garage, so it’s a lot more poised and slick than the hardcore/jungle style, and yet there’s continuities, the use of the vocals, the air of hysteria, and also there’s a kind of hyperkinesis to the music, even though 2step’s dancing tempo is approximately half the tempo of hardcore, it’s got all these twitchy elements, it’s almost as though the speed and convulsiveness of hardcore and jungle has been imploded into the music.

Now if you were to look at these guys, Steve Gurley and Chris Mac from a distance, if you didn’t know anything about this area of music, you might say “goodness gracious me, what opportunists these chaps are, they jump from one style to another, where’s their artistic integrity?”. But they are just going with the flow of the continuum, carried along by its currents, and the point of the continuum is, it doesn’t stay still, ever. Indeed you stay true to it by being stylistically faithless–inconstant.

And finally here’s another recurring figure, someone who keeps moving and grooving all through this period, a fellow called Grant Nelson. Under the name Wishdokta he did a lot of rave tunes for the label Kickin’ but from what I understand he was already making UK garage tunes in the early to mid nineties–closer to the US model of garage, nothing like speed garage really, but still, precocious fellow, eh? And during the mid-90s he was making happy hardcore, in partnership with a guy called Vibes who was the biggest happy hardcore DJ at one point — so Grant’s got fingers in many pies. Instead of a Wishdokta tune though I’m going to play a track by someone else that Grant Nelson produced– Xenophobia’s “Rush in the House”–for reasons that will become apparent.

Xenophobia, “Rush In the House”, Kickin’ 1992

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ofnmh1pgWzE

Cheeky stuff!

So Grant Nelsons’s enjoying a lot of success on the hardcore scene and happy hardcore but in ’97 he really makes a name for himself with fabulous speed garage anthems under various names. Like this one:

N&G, “Liferide”, 1997

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=efEpnOSa4ug

That features Rose Windross, the sister of Norris the Boss Windross, and she sang with Soul II Soul early on — the MC is Creed, one of the great UK garage MCs. But you see why I played Xenophobia, cos that track had an MC, MC Scallywag, rapping about Ecstasy. And you see how the MC thing runs through the whole of the continuum. And with UK garage you have all these star MCs like Creed, but what’s significant about “Liferide” is that Creed is rapping some proper verses in that song. It’s no longer just a few catchphrases. And you get more and more MCs doing that over garage and 2step and that is the beginning of grime.

One more from Grant Nelson, as Bump N Flex he did this 2step monster in 1999

Bump N Flex featuring Jean McClain, “‘Step 2 Me”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0LQgwgz7EDE

Now when speed garage happened you could say it was American house music momentarily overpowering the continuum to an extent, but with 2step the jungly, UK-only thing reasserts itself. Here on “Step 2 Me” it’s like jungle and house are fighting to control the track. That bass drop is just pure junglism, I can’t tell you how many tracks in 95 and 96 had a sort of rolling feel to it. And then fighting back, you get that flickering keyboard lick coming in that’s pure garage. But also there is a really brief sample of Foul Play, a tiny snippet of synth from this gorgeous track they did after Steve Gurley left, ‘Being With You’ from late 1994. Now why would Grant do that? It didn’t really add much to the track — well, it’s there for those who know, it’s deliberating emphasizing the continuity for the community. And ‘Being with You’ is a classic soul-powered diva jungle track, sampling Mary J. Blige, if I remember right.

Now there are those who would say “well, look these so-called continuum producers, they’re sampling R&B vocals, with 2step they’re nicking rhythmic ideas from Timbaland, early on you had influences from hip hop, you’ve got reggae and dancehall as a constant feed-through of ideas. You also had Belgian hardcore techno as a big influence early on and it keeps cropping back with techstep drum’n’bass, even with early grime.”

They would say, “It makes no sense to isolate this strand of UK music separate from what’s going on in the wide world of music.” And if they’ve read some Deleuze and Guattari, some Sadie Plant–and they usually have–they’ll say that a much better way to see music is rhizomatically, everything connects to every else, all music is connected to all other music. Music’s not about roots, it’s more like a bed of nettles, it works through lateral connections. Rhizomes — in the horticultural sense.

To which I retort, well obviously these people are influenced by stuff outside the continuum, how could they not be? We’re all of us inundated from pop music from every side, and these are musicians, they’re sensitive to this stuff, they’re going to be turned on by new ideas wherever they’re from.

But the key point– and it’s so obvious really–is that when these people in jungle or garage or grime or bassline make their tracks, who are they making their tracks for, in terms of an audience? And who are they making their tracks against, in terms of who is their competition?

DJ Hype might have sampled people like the Wu Tang Clan and G-funk, but when he made a track he wasn’t thinking of competing with Wu Tang Clan or Dr Dre on their terrain, that wouldn’t be realistic and that wasn’t his goal. DJ Hype’s focus was on making a tune to spar with the latest production by Andy C, Ray Keith, Asend –people on the jungle scene.

And Wiley and Dizzee and other grime people, for sure they’ve listened to American rap. They’d dig certain US rappers and they’d steal rhythm ideas and production ideas from Swizz Beats and Neptunes and other street rap producers from the States. But when they make a tune they’re not trying to compete with those guys, that terrain is way way out of their reach. No, Wiley is sparring with other grime producers like Terror Danjah or Lethal Bizzle. That is their battle zone–the grime scene.

So that is one way to conceptualise the continuum: as a contest, a competition, a game. Like a sport even. Indeed this music actually has rules, it’s not a free for all, not at all. Producers on the scene sometimes spout that kind of talk, about how there’s no rules in this genre, “we can do anything”. But in actual fact if you look at the music at any given point, it is quite tightly formularized. Tracks have to be within a really quite restricted beats-per-minute range, they had to have a certain rhythmic feel; if you didn’t have, say, particular drops in the track, DJs couldn’t use them. So at any given point there was a range within which you operated, and creativity was bending those rules, not breaking them. It’s easy to break the rules, easy to totally disregard the functional requirements of the music.

This is how the hardcore continuum works, and how all continuums work. Through the pressure of peers: a spirit of mostly friendly, occasionally vicious rivalry between people who more often than not know each other. In the early days of writing about jungle I hung out with Goldie a bit and I was always struck by how often other producers seemed to figure in his imagination in this almost phantasmic way, like he was engaged in one-sided wars with people who might not have felt the same about him at all, or even been aware there was this competition going on. Goldie talked about how he was competing with a guy called Cool Hand Flex, a producer who’s hardly remembered now. Now perhaps Goldie felt threatened ‘cos Flex was doing a few tunes that had a jazzy fusion element, which Goldie felt was his agenda with songs like “Angel”. So Cool Hand Flex would be encroaching on what was going to be his territory. And Goldie alluded to having had similar sparring feelings towards Foul Play and DJ SS at certain points, and also a really obscure outfit called Bodysnatch. At the same time these were people he rated highly, as the competition, the guys to beat.

But it’s actually the same in most music scenes if you look at the history of music — in the Sixties the Beatles, Stones, Beach boys, were all checking out each other’s stuff, trying to race ahead of each other, responding to or stealing each other’s ideas. If you read Alex Ross’s book on 20th Century classical, figures like Mahler and Schoenberg, you see these composers often knew each other personally, they followed each other’s work with very keen interest, it was about keeping up with each other, outflanking each other, sometimes taking each other’s ideas and doing them better.

And perhaps this is a good point to point out that this hardcore continuum is just one continuum among many in music. You could talk of a jazz continuum, or multiple jazz continuums. A metal continuum. The UK hardcore continuum isn’t the only continuum in dance music either, you could talk of a trance continuum, a deep house one, a minimal techno one, a number of other dance continuums. It’s even not the only dance continuum I’m interested in as a listener or as a writer, for instance I’ve written a lot about another music called hardcore, the gabba tradition, European four to the floor kick drum pounding terror techno, I’m a big fan and defender of that. And that other hardcore is pretty separate from the UK hardcore continuum, although they intersect at various points. But you know I’ve even had some kind things to say about trance at certain points! But some people seem to get this idea that this music is the only thing I value, which isn’t true even in dance music, let alone the whole world of music. But I would say for me the hardcore continuum is definitely the most consistently thrilling and thought-provoking strand of British dance music.

It’s also never been my contention that this hardcore continuum is sealed off from other music, that it’s this impermeable thing. Influences seep in but they are assimilated — they become fuel for the furnace of a struggle between peers for supremacy, to be the don of the scene.

So I would further argue that a healthy musical continuum is one where everyone involved is listening to everybody else very closely, but they’re not ONLY listening to people inside the scene. They’re tuned to stuff outside it, and then they use that stuff from outside as part of their arsenal against the other producers within the scene who are their rivals.

An unhealthy continuum is one where people are listening closely to each other, but they’re ONLY listening to each other. That happens a lot with musical traditions, they become enclosed, purist. That might well be what happened to drum’n’bass after 1997.

But talking about competition, rivalry, jousting — let’s move onto rival theories, different ways of mapping how music works. Now I could hardly fail to have noticed that recently there’s been some people who’ve been kvetching, grumbling a bit about this idea of a hardcore continuum, on the ground that it’s maybe overly… legislative, perhaps is the word. And some of them are proposing this counter-theory I referred to earlier, the rhizomatic, everything-connects-to-everything-else outlook. Now to be honest this seems a bit dated to me, it’s very 90s, very Mondo 2000, it makes me think of that period when you could get smart drinks at rave. But the main thing is that I think this theory appeals to certain people – those who happen to be DJs or producers — because it casts their artistic practice in a flattering light. They can be the brave, free spirited artist who isn’t chained to a particular scene or style. Once upon a time people like that were known as gadflies, dilettantes! But the thing that interests me about this particular theory — if you can call it that, because there’s not much to it — is that it instantly deconstructs itself. These people are dependent on the existence of genres as relatively stable entities so that what they do in terms of mixing this and matching that — yawn, it seems so un-enticing really doesn’t it? — can seem audacious and naughty and clever. They would not even exist as artists without these genres whose boundaries they purport to scorn. Not only are they literally parasitic on all these genres — the hardcore continuum genres, the shanty house genres like carioca funk and kwaito and juke and baltimore breaks, what some people call the global ghetto tech genres –but they are philosophically dependent on them. The valorization of unrootedness, or uprootedness, is dependent on the existence of the rooted, which can be denigrated in comparison to their marvellous mobility and freedom. It’s perfectly obvious why they wouldn’t want to to go along with a theory that emphasizes continuity through time and an element of geographical groundedness.

Now I do try hard to be fair so I’m going to attempt to see why those theories and the artistic practice that accompanies them might appeal, where its element of idealism is. And I would say that it relates to a utopianism of space–that’s really what makes it so 1990s, so early days of the web–the idea of connectivity, of postgeographical flows, of things that are remote being brought close, the separate and far-flung become one in the mix.

Now the hardcore continuum operates through a different kind of utopianism, not constituted through space but through time. Oh, it does have a romance of place–the Just 4 U London thing. But I think time is the crucial axis. I always come back to this phrase I use a lot, the title of a track by a hardcore outfit called Phuture Assassins: “roots ‘n’ future”. If you look at the hardcore continuum you can see a consistent impulse running through it that simultaneously casts backward to the past and forward to the unreachable horizon of the future. So you have roots, and roots in the most obvious sense mean Jamaica and the sound system tradition, but also, and I’ve noticed this with people in this scene, that when you interview them they often have a sense of legend, a sense of a hallowed and halcyon past, they’ll talk in misty-eyed terms about raves or tracks from long, long ago, meaning five years ago — like one of the flyers showing on the screen, don’ t know if it’s been projected yet, is for a Back to 91 Rave, but it was a Back to 91 Rave that took place in early 1995… so that’s like only four years previously! And often producers and DJs and MCs when you interview them see to have a sort of grand sense of themselves as heroic figures with storied, glorious pasts, these are people who are sometimes only 22 and they’re talking about “back in the day”, about things they did when they were seventeen, their first tracks they made or spat on.

But there’ll also be this thing all the way through this culture of reaching out to tomorrow, “living for the future” as Omni Trio put it. Or, “We bring you the future, the future, the future” by Noise Factory. It’s like people in the scene having a heightened and highly charged sense of temporality…

This utopianism of time is something that threads through the culture in strange loops because when you listen, as a fan, to stuff from all across its breadth and length, you sometimes get these uncanny timewarp sensations–you hear things in 1990 bleep tune that are future-ghosts of sounds in grime or dubstep or bassline. It’s almost like any track from any point in the continuum contains all the past and all the future of this music inside it. Like DNA or something.

And then as well as these accidental echoes, you also get deliberate homages in more recent music harking back to the old skool days. Burial’s music is only a self-conscious, scholarly version of this syndrome.

So I’m going to play some examples of this kind of homage:

Jonny L, “Hurt You So” 1992

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WppBZkp7WUM

This was one of those hardcore rave tunes that people expected would be a hit, it was massive on the pirates, had all the potential to crossover, but it didn’t.

So Jonny L goes off and does various things, disappears for a bit, then comes back in 1996 doing this sick, punishing, ultra-minimal drum’n’bass.

Then speed garage happens and we get this record

Fabulous Baker Boys, “Oh Boy”, 1997

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jr49WEV4VFU&feature=related

So you have the same vocal as in “Hurt You So” and there’s other melodic elements and arrangemetn motifs of the original tune reused too. There’s a couple of aspects to this: one is just recycling, a good tune is a good tune, but also I think there is conscious homage, because there were loads of hardcore remakes done by speed garage and 2step outfits. I almost think of them as being orientation devices for the scene, there’s been this massive paradigm shift to a much slower kind of groove with speed garage but this is affirming that it’s still a continuum, in fact it may even be saying UK garage is more true to hardcore than drum’n’bass in 97 was, because speed garage had the blissful female vocals and drum’n’bass had dropped the vocal science element, the divas had departed from drum’n’bass completely.

Now Jonny L notices his tune’s getting reworked and he plunges into the 2step garage scene doing stuff under the name Truesteppers, with this guy called Andy Lysandrou, who used to be a hardcore producer under the name Kid Andy. And then the Truesteppers name really takes off with this single “Out of Your Mind” featuring Victoria Beckham and–Autotuned to fuck–Dane Bowers. And this record got to Number 2in theUK charts in 2000!

Truesteppers featuring Victoria Beckham and Dane Bowers, “Out of Your Mind”, 2000

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4KWXbQwt-bI

So Jonny L finally gets his hit record…

And what an amazing production, you can hear the nasty bass sounds that are pure techstep drum’n’bass, and little bursts of jungle style breakbeats, chopped up Amen breaks that are pure 1994 Amen-smashing junglism, and also that little orchestral snippet running through the whole thing, like I said a running thread through the whole continuum, this sub-classical penchant.

And what makes it even more interesting for me as the nutty nuum scholar that I am is the involvement of Kid Andy, he had founded a hardcore rave label called Boogie Beat way in 1990, and in 1992 I remember something really unusual, you had ads on the pirates mostly for upcoming raves, almost never for a track that was coming out but they had an commercial for a new tune from Kid Andy and Nickelbee called “Pain”, they clearly thought it was going to be massive, everyone would run out to the shops and buy it and it would get in the charts. And “Pain” was basically George Michael ‘Careless Whispers’ over a breakbeat. George was still a pretty massive pop star then. And in a funny sort of way that Kid Andy fantasy comes true cos he’s essentially slung a riddim track under Posh Spice — who in 2000 is probably the biggest pop celebrity in the UK, just post Spice Girls this is, and they had instore signing sessions all over the UK for “Out of Your Mind” with Posh and Becks signing the single. But what really interests me is why she did it? Why did she get involved in a record that would otherwise have been a pretty underground tune? Well, it shows the power of the hardcore continuum, 2step was so massive in 2000 it was a good move in terms of credibility, she wanted to be part of it.

And just briefly as an aside, here’s a little burst of what Jonny L was doing immediately before going 2step — “Piper”, his techstep drum’n’bass classic

Jonny L, “Piper”, 1997

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3qo1aoR96oI

Now interestingly there is a female vocal in here but it’s completely devoid of soul, Dalek-like, dead, just like the groove which is this lifeless, if quite impressively stiff beat. This style of drum’n’bass — neurofunk is what I called it — is basically the music that made speed garage need to come into existence. And from speed garage we get dubstep, we get grime, we get bassline, we get funky.

So now we move to the stage I alluded to earlier, beyond the facts, beyond even the analysis and the theorization, towards the claims you can make for this music. My final oration, as it were.

People ask me, “why are you so obsessed with this music Simon?” At first I’ve nothing to say, it’s self-evident isn’t, just listen to the music, I could just have not said a word and played you 20 tunes and you’d have understood, I’m sure. But I can’t get away with that, and I’m not a deejay. So, okay, here why it’s so important. There’s two sides to this, the objective and the personal.

Objectively, I stake my claim here that this music has been our equivalent to hip hop and our equivalent to reggae. By which I mean, a musical system that endures while evolving at an insane rate. If you look at all the changes hip hop’s been through, from the late 70s to the early Noughties, it’s incredible, or look at Jamaican, the journey from ska to rocksteady to roots reggae and dub to dancehall to ragga — unbelievable. And interestingly just like the hardcore continuum, hip hop and Jamaican music also have this “roots ‘n’ future” thing of referring back while always looking forward. So there’s a utopianism of time, maybe even a messianic conception of time: the promised land that is behind us and ahead of us. And this obviously relates to aspects of the black experience, and also to Christianity, the mystical strains of Christianity as they’ve fed into Rastafarianism and into the Baptist and Pentecostal traditions in America that had such a big influence of Black American music.

Now I love hip hop, and I love reggae and dancehall, but I couldn’t be part of them, I’d always be loving them from the outside. Whereas the UK thing, for all its roots in mostly black music and its background as mostly –not exclusively– but mostly working class culture, the UK thing has been something I could be part of.

So I can say truthfully this is the greatest musical thing I’ve ever witnessed with my own ears and my own eyes. I mean, I love Sixties music but I was small child then. I wasn’t a small child during postpunk but I lived in a small town and a lot of it I missed, as subculture, there weren’t many gigs where I lived, most of the key bands of the era I never saw perform, so postpunk was mediated through records, the radio, the music press. But the hardcore continuum, I experienced the early years of it and even after moving to America was still able to dip into it as a full experiential participatory thing on a regular basis.

So that brings us round to the personal aspect, which is not a claim but just pure testimony. What can I say? Outside my wife and family, I ‘d have to say this music has given me the best years of my life.

The hardcore years… just crazy adventures, a rollercoaster of experience, I was disoriented, hurled into this vortex, barely understanding what this music was. I never went to clubs to see particular DJs I just went along for the adventures you’d have.

Then the jungle years, by this point it was more mapped out, I was more aware and informed — I’d say my mode shifted by that point to being a scholar-soldier –that’s the second phase of music fanaticism, when you start to know who the auteurs are, the DJs and the producers and the key labels, you’re piecing together the history of the scene. I was a fanatic, a patriot, for jungle — and I would have put junglist on my passport at that point.

And then speed garage — what that was like was, imagine you were in love with someone, you thought they were beautiful beyond compare, you loved all their little mannerisms and expressions, quirks and secrets… and then you woke up one morning, and your lover had turned into a completely different person, just as beautiful, as adorable, but with different features and quirks and mannerisms, BUT underneath somehow the same person, the same soul. Quite disorienting, to wake up like that, but then equally a wonderful gift, the opportunity to fall in love all over again without losing the thing you originally loved. So that was speed garage, jungle in new flesh, jungle reincarnated.

And then 2step… Now if you love someone, you want the best for them,right? If my wife was suddenly made the editor of Vogue I’d be so proud and pleased for her. Well, that’s what it was like when 2step, after 18 months bubbling on the overground, just completely took over the pop charts in 1999 and 2000

And grime…. That was like waking up in the morning and finding your partner has turned into Godzilla. And yet you still love her, it’s still the same soul underneath the monstrousness.

I’ve possibly extended this metaphor perilously far, but you can see I identify with this culture very strongly, I feel wedded to it.

With my music critic’s hat on I think of it as musically the most impressive thing to come out of the UK in the last couple of decades. And with my cultural critic’s cap on, I think it’s in a lot of ways the most hopeful thing that’s come out of the UK’s multiculture.

And yet for all that I wouldn’t be devastated if it just crumbled away, as it might well do, and sooner rather than later. It has had a very good run, it really is 20 years now, if we think of Unique 3’s ‘The Theme’ coming out in 1989. That is a long time for a musical formation to hold it together and stay interesting. Does it have new surprises up its sleeve, or is it going to disintegrate into different directions? It could split up into separate streams that go their own merry way, and some of them might merge with other musical traditions.

Funky is the first thing ever from the continuum that I’ve not been swayed and slayed by, it’s where I feel like maybe they’ve left behind too many of the key elements from the mix. It’s a bit too tasteful for me. I’m biased in London’s favour, I’m a London patriot generally, but I really feel like the last few years the North has been carrying the banner of the continuum. Bassline has everything that I most love about this music: the rudeness and the cheesy-ness, it has the bass madness and the MCs and the blissful female vocals. So in a lovely sort of way that is a circle being completed– back to the bleep days — to Sheffield Leeds Bradford Nottingham running things again.

So I want to end my talk and set up the next bit with Mark Fisher by playing a tune that is totally London oriented, the tune is by Gant and it’s called “‘Soundbwoy Burial”, a speed garage classic from 1997.

Gant, “Soundbwoy Burial (187 Lockdown Dancehall Mix)”, 1997

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tDgNZgM75e8

But interestingly if you go on YouTube the person who posted this tune describes it as speed garage but also as a Niche anthem — Niche in Sheffield being the legendary foundational club for bassline house. So this track which is so London oriented, the MC starts by calling out to the four corners of the city, North East South and West, yet it is an ancestral tune for bassline and for the whole Northern extension of the continuum. It’s a hinge track, for me, it came out almost midway in the historical span of the continuum, and in it you can hear things that cast back to bleep, ardkore, jungle, but also things that look forward to grime, dubstep, to bassline — obviously, with that crazy warped bassline — and maybe even to the slinkiness of funky.

That’s why they call it a continuum folks!

Nuum spectrum disorders

Posted by homoludo on Feb 27 2009

Posted by homoludo on February 27th, 2009 filed in Hardcore continuum, history, theory, writing

3 Comments »

I posted last January 08 that a blogging bitch fight was about to begin. What was being contested was the use/aplicability of the hard core continuum model. The fight never really kicked off and I felt foolish and petty and assumed everybody else was more mature. Now, to my gossipy delight, it turns out they’re not, they were just biding their time and it has begun, with these(1, 2) posts from K punk and this and this and this from Simon Reynolds and these from Splintering bone ash and this and this from Kode 9 and this from Dan Hancox at fact(ok I’ll stop, oh no I wont’) this from uncarved. Beyond the schoolyard fun of rushing to view the ‘fight! fight!’. There is good thinking and writing going on about current bass/dance music.

Reynolds and K punk are being a bit silly and bulldoggy attacking wonky. The hcc is a good and useful model but, it gets less interesting when used as a stick to beat things that don’t fall into it(also models aren’t real). Claiming things aren’t as good as they once were is not that interesting.

How good or bad wonk, funky or bassline are and to what extent they fit in the hcc is an angels on pin heads issue and is a nostalgia mode in itself.

Mr splintering bone ash is the one nailing it best – What is lacking is not as he points out a

‘failure of modernist will.’

and his observations on the modernist need for innovation are on point.

Also, he points out that ‘breakbeat can only be absorbed once’

Following this samplers, time stretching etc are only new once.

Other reasons the first wave was so hardcore were; E use being new(it was a big deal), Dj’ing (as a mass entertainment), the fall of the Berlin wall and the party that followed, the huge numbers on the dole(15% in Ireland in 93 – that’s a lot of people available to rave, ), Top of the pops and massive tabloid interest, a well developed anti Thatcher counter culture(lots of whom fled to Ireland) leading to free parties and rave being a politics, which punks etc took up. Also there were LOTS of house parties( this should not be underestimated, and I’m beginning efforts to resurrect this culture, what else to do in a recess? Stay tuned).

These were events and peoples responses to them, it was not willed.

That’s what strange about Reynold’s and Ficher’s positions, for writers steeped in materialism they seem to be ahistorical and vitalist about this. What is more interesting than what fits or does not fit in the hcc, is to look for what is different now and if you don’t know, you’re not looking in the right places.

It’s so different it makes my head hurt(in a good way) and it’s still the best fun I know.

(post)Modern Milli

Posted by homoludo on Feb 08 2009

Posted by homoludo on February 8th, 2009 filed in riddim, theory, video

Comment now »

from Wayneandwax with the boys getting into theory in the comments and also here with Birdseed taking apart a milli’s structure. The instrumental is even better.

Mash of the week 9# Gash up. Yes, but is it art?

Posted by homoludo on Jan 23 2009

Posted by homoludo on January 23rd, 2009 filed in !Kaboogie, mash of the week, mashes, mixtapes, music, theory, writing

3 Comments »

Here’s the Banker getting on board the train to mashville with- ‘Gash Up’, an extraodinary mash/edit/arrangement of -  M.I.A. – Galang Acapella, Aphex Twin – Jynweythek Ylow, Shackleton – Tin Foil Sky, The Banker and Beethoven – Adagio Sostenuto. Check the way he uses the piano from Beethoven’s Adagio against M.I.A’s voice then segues into the Aphex twin piano…gosh.

[audio:/Gash_Up.mp3]

Speaking of mashes here’s a great, interesting and thought provoking piece by Nick Sylvester and W. David Marx on Girl Talk. For those who don’t know, Girl Talk does fairly dense mashup albums.(He’s playing Dublin in March, I think I may even be supporting him)

Quote

…the extent to which the music he’s working with is so portable, so building-block ready, makes it seem like he’s not making art so much as merely following industry directions: Step by step, like he’s putting together a Lego spaceship. There is no violence in this process, in other words; he’s hardly repurposing much of anything. Instead it’s like a video game in which Gillis has found the warp level — yet keep in mind, somebody somewhere had to program that warp level precisely so that it would be discovered.

On a boat on the Shannon last summer listening to the Girl Talk album with my friend the film maker, Eamonn, I got him excited by suggesting that a program could be easily written to mix and mash tunes by their key and Bpm. I’ve since came across Mixmeister which pretty much does this and it’s a matter of months before it or something similar is used as a plug in for media players.

The piece makes some interesting points and is a good read, though quoting Adorno to the effect that pop isn’t art muddies the waters. The pop he was talking about was Jazz and tin pan alley etc. It’s also a bit unclear what their problem with Girl Talk is – that he claims to be an artist? That he’s ‘only’ a technician?

The problem here is the usual one that the word art doesn’t actually mean anything.

From the hitch hikers guide to the galaxy

Generally, art is a human activity, made with the intention of stimulating thoughts and emotions. Beyond this description, there is no general agreed-upon definition of art.

–So every thing apart from work then.

Art used to glorify God, now it glorifies the market. Either everything is art or nothing is. I’d go with nothing. Good stuff, bad stuff, stuff I like, stuff that suits my agenda, but don’t go putting wings or halos on any of it.

It’s important to bear in mind the contexts of mashes and the processes that produce them and with that the fact that they create their own contexts. I remember in the days of Boomselection thinking mashes were done, but they keep going, to the point they are now a model for new technologies. Saying they are soulless is a bit of a so what?- That isn’t nescessariliy a bad thing. We’ve just had over twenty years of dancing to a drum machine and searching for the smallest atom of funk…which has been good fun.

To what extent is Coltrane’s ‘Favourite things’ a mash? Anyway read the piece, it’ll get you thinking. More mash theory here.

In other news here’s a link to the front page on Indymedia about a mash(projecting images on a building) I took part in on Monday. Organised by the above mentioned Eamonn, It took place outside the Israeli embassy.

PCPRaidio_Pixie house

Posted by homoludo on Jan 18 2009

Posted by homoludo on January 18th, 2009 filed in music, paranoia, radio shows, theory

1 Comment »

Okey dokey, did this show before crimbo but radio closed over the yule and just got it up. Starts with some cheesy Baltimore/diplo/dress to sweat etc. house , check Diplo’s Pixies cover- effective. Second section is tuffer, starting with a very cool one from the amazing Daedalus into couple of big tunes from Raffertie, who’ll be joining us in April despite the closure of McGruders(the one that got away), some of the chat about which is here.(Edit- this page wasn’t displaying properly, it should be ok now.)

1. Rod Lee – Let Me See What You Working With

2. Diplo – Blow your head

3. Rod Lee – Let Me See What You Working With -Rustie remix

4. Diplo – Devil between us

5. mia??

6. Pixie boots (gauge away remix/bootleg)

7. Daedelus- Fair weathered friends – the death set refix.

8. The Debonair One – The bmore 20220

9. Daedelus ‘Hours Minutes Seconds (Beat Invitational Version)

10. Food for animals – Mutumbo Raffertie’s Bigger bass remake (unreleased)

11. Raffertie -Â Stomping grounds (rafferties VIP Remix)(unreleased)

12. Peter Gunn and Small change- Pacman’s on some syrup

13. Mr V – Mother Fuckers

14. ???looking

15. Moves- All skate

16. Starkey- No Struggle

17. Dj Funk – Booty clap

18. Kid Cudi feat Collie Buddz- Day and night

19. Cotti feat. Doctor -Â Calm Down

20. War 7 – Polizia mix

21. Untold -Â Bones

22. Mordant Music -24 Million Or Sell Neverland

23. Sillicon Scally – Request – Wee dj’s mix